|

I can only imagine what you are thinking sometimes. Once again, our profession is in the news over a middle school teacher accused of having sexual relationships with two students. Unfortunately, it’s happening in my own district. I cannot express how frustrating these moments are to me as a professional, and I can only imagine how frightening they are for you, as a parent. For that reason, I am going to ask a lot of you. Don’t lose faith. Please. I need you to rely on better models of who teachers are – not the Larry Nassers and the Harvey Weinsteins of the profession. Rather, the number of amazing teachers I work with and read of every day. So I put together some evidence – some proof – that for every bad teacher there are 100 more great ones. I’ll start with a familiar video. This guy makes a handshake with every one of the kids that walks into his room. It’s a marvel of memory, but it’s an incredible representation of the healthy relationships this teacher (and so many teachers) create with their students. Another often seen video – at least by other teachers. Rita Pierson embodies what it means to advocate for kids, what it means to go to bat for a kid’s best interests, what it means to care. I have seen teachers go to unbelievable levels to make sure their students have what they need. Just skim through DonorsChoose to see all the teachers investing time and energy into new learning experiences for students. You’ve probably heard of The Freedom Writer’s Diary or seen the MTV movie with Hillary Swank. Erin Gruwell, the teacher behind the story, incredibly sacrificed so much for the students in her class – her time, her money, her marriage. I am constantly inspired by the sacrifices I see teachers making for their kids. My next example comes from my very own department. My department chair is an incredible woman – just in general – but an even more amazing teacher. One thing she did this year that continues to inspire me is she paid for one of her student’s lunch. But, like I mentioned, for every Beth, there are a 100 more just like her. They buy hundreds of dollars in supplies, buy their own classroom furniture to produce flexible seating, pay fees for activities or exams, and more. And they do it for the love of your child. Your children’s teachers are their teacher for life. The support, encouragement, and hope they have for your kids never goes away. Another colleague of mine witnessed one of his students struggle against an emotionally abusive father who would eventually kick him out of the house. The next year, that teacher paid for his books to get him through his first year of college. The amazing part is he is one of many teachers who have done the same for their students. I could go on indefinitely, noting all the times I saw a teacher make a student smile, sitting in their office late into the evening, or cheering from the bleachers. And those are the teachers that become angry in situations like that at my own district. We are enraged that someone would ruin the trust we build with parents, students, and other staff by sullying the reputation we all work so hard to protect. And those are the teachers that understand your anger, fear, and outrage. Please have faith that there is more good than bad in the teaching world because it’s there. I promise.

1 Comment

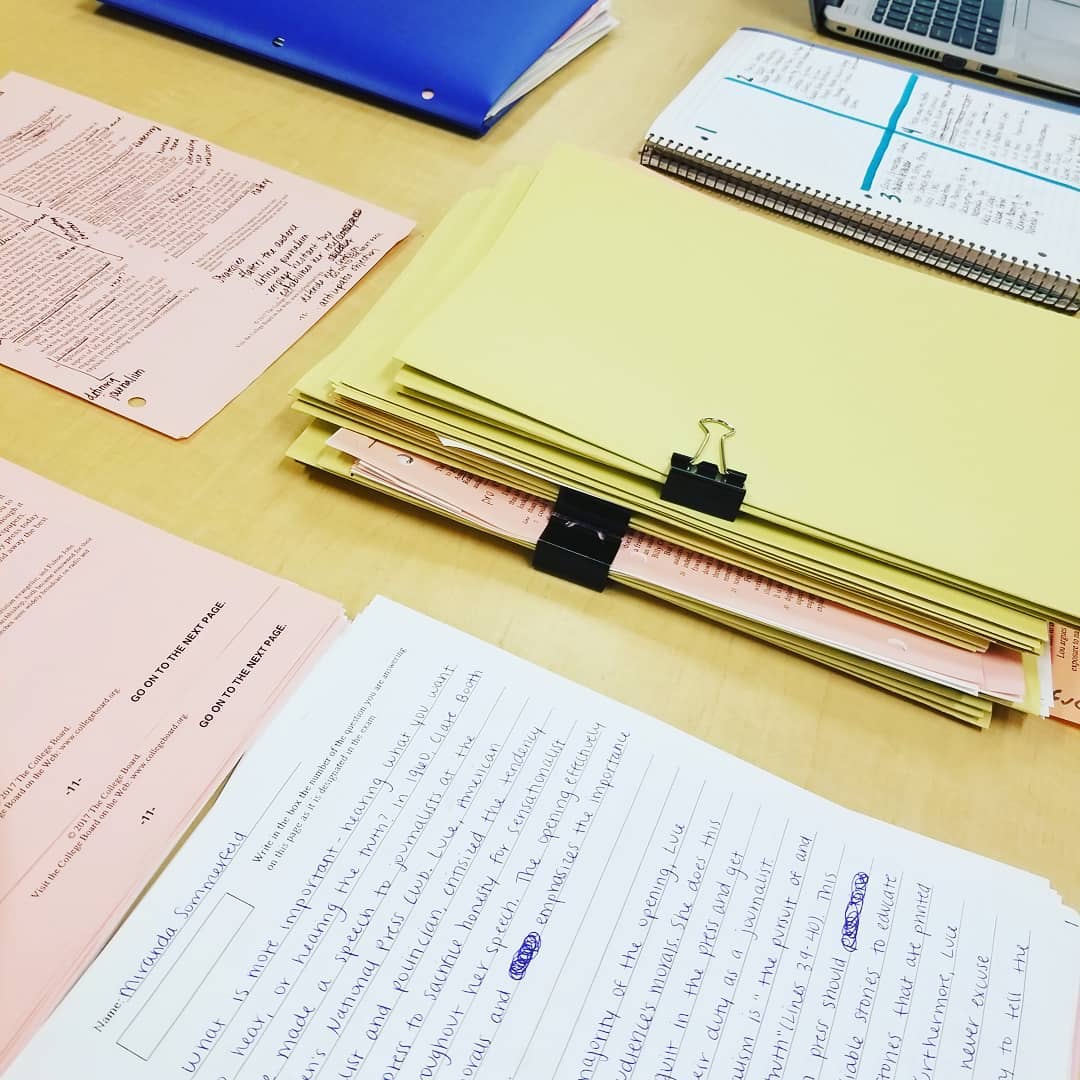

You’ll have to forgive me on this last post of my series on grading. As much as I want to spill everything I know on process grading and daily work, I have to be brief. Manfriend and I put an offer on a house last night which means at any given moment, I will get a call which means we have THREE days to prep our house for sale. (Probably should have started finishing little projects when we started looking). That said, I am excited to talk about Grading Hack #5: Process Grading and Daily Work. I’m going to start with a truth that becomes more obvious as the years go on: You can’t grade everything. As a first year teacher, I was convinced that the only way to motivate kids was to assign points to something. Time has taught me otherwise. Now, I am convinced that if I am able to grade everything my kids hand in, they simple aren’t doing enough – especially with writing. However, I teach AP students, and if you do, you know how driven they are by grades and points. It’s a constant stream of “Is this on the test?” and “When is this due?” [Side note: As I care less and less about points and deadlines, the constraints of grading become as philosophically demanding as the actual scoring.] For the last two years, I have adopted a method of managing daily work that has kept my grading very manageable, and as a bonus, kept students organized and provided additional resources. Its my hybrid between the all-powerful binder and an interactive notebook. ap bindersEach year, my students are asked to bring a binder with page dividers by the end of the first week. I provide them a set of what I call the “Yellow Pages” - which I “borrowed” from another AP teacher. This includes general resources like AP Free Response Question overviews, sentence models, and their progress monitoring form. In addition to these pages, I ask students to put loose leaf paper in the back.

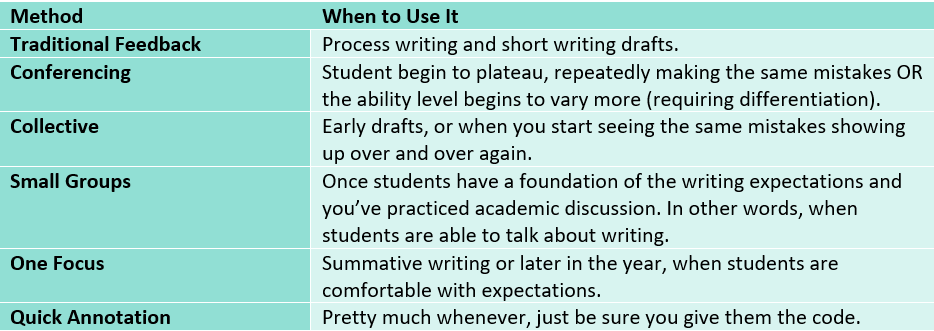

Every handout I give them is hole punched so they can collect all the materials in their binder, and the loose leaf is used for writing practice and daily work. Pretty simple, really. The binders stay in the room when possible so that things do not get lost (as often…). Every so often (maybe once a month, every other week, etc), I tell students four daily work activities or handouts that I want to check in their binder. It takes about 10 minutes (usually during reading time) for me to swing around the room checking off the student’s work. I know class time is precious, but it really does take less than 10 minutes, even with 30 students. In essence, its just a quick check for completion using the method. If I want to actually assess work, I will do a check outside of class providing feedback. I have also – at times – allowed students to pick one of the four drafts to submit for a grade. In other words, the assessment of material is flexible depending on whether I need to deeply analyze student work or just check that they are on track. The added bonus of this organization system is that students never know what is going to be checked until the day before. They are motivated to participate in all activities as they are unsure which will be connected to their grade. Then, the day before, they can go back and add detail to those which will be assessed. And that's what I have time for. (Sorry!). Short. Sweet. Time-Saving! So my second way to cut back on grading is self assessment, and the good news is, I already posted on it! Check out how I embrace self assessment in my classroom to alleviate some of my grading here, in my Dear Grading, You Suck post. With that all wrapped up, I can move on to Grading Hack #4: Feedback Methodologies. (Sounds like a party, doesn’t it?) You may be wondering, how do different methods of providing feedback lessen my grading load? In fact, doesn’t additional feedback increase my time spent grading? I’m here to say it doesn’t have to. Most of the time we spend grading is usually dedicated to comments and notes we add to drafts and assignments to move kids in the right direction. This, in my opinion, is the most traditional type of feedback, but not necessarily the best method. To cut back on some of the time invested in this step - and therefore, cut back on time spent grading – I have adopted different methods of providing this feedback that move things a little quicker, and again, in my opinion, produce more significant student growth. Let’s dig into the methods I want share with you by comparing them on the time scale. I created a fancy little infographic to illustrate the time invested in each method. Forms of Feedback (by Time Invested)As you can see my methods vary in time investment, but all belong in effective writing instruction. The hack comes in knowing when to use each effectively. Let’s begin with the most time consuming ones: traditional feedback and conferencing. Traditional Feedback: There is nothing wrong with taking the time to write rich commentary on student drafts. In fact, I see this as a very important starting point with my AP students. I do, however, use it sparingly, and most commonly, with process writing. As I build students toward a full AP Free Response Question, I will provide this detailed feedback on outlines and paragraphs (and nothing longer than that!). In all honesty, I reserve this method almost exclusively for the collaborative writing I discussed in my last point. When they are short or fewer drafts, traditional feedback is manageable and effective. The traditional detailed annotation of traditional feedback is powerful; it just needs to be used in a feasible context. Conferencing: Requiring the same investment of time as traditional feedback (possibly even more), conferencing also has its place and is probably the most powerful with young writers. When surveyed at the end of the year, the highest percentage of my students found conferencing most helpful in improving their writing. As we all know, though, the amount of time needed to effectively conference with students is incredible. Last year, I recall setting aside three days of class time for conferencing, only to find out I could maybe get through about five in a day – unsuccessful with a class of 30. Similarly unsuccessful (or more so, impractical), setting up conferences outside of class completely devoured all my prep time. Nonetheless, conferencing has to happen in a writing focused classroom. Just like with traditional feedback, I have found that it is simply about finding the appropriate time to utilize it. This school year, my fellow AP teacher and I agreed to a schedule where every other week, we’d send out a Google doc with conference time slots for the kids to claim. These were weeks following timed essays (AP FRQs) so that students could bring their most recent, scored essay for one-on-one discussion. Limiting the conferencing to every other week kept it more manageable as we could plan our prep time accordingly. We also offered this option primarily in the middle of the year: quarters two and three. After discussing when this method would be most impactful, we decided that they needed to begin with a basic understanding of the material before conferences would even be practical; hence, we didn’t send out the sign ups first quarter. Then, as we got close to the AP exam, we wanted them to be more independent in their evaluation of their writing, so we stopped sending out the sign up sheet fourth quarter. At any point, I encourage my kids to come see me about their writing, but this created a period focused on conferencing that was much more practical than attempting it all year long. As for as the practice of conferencing, there are people much wiser than me on the topic to guide you (See: Write Beside Them by Penny Kittle). My method - which fortunately requires no prep - has usually been to read through the essay with the student, stopping to discuss weaknesses and strengths. Students can amazingly hear the issues in their writing as soon as it’s read to them. Moving on, the next two methods – small group and collective feedback – have proven to be incredibly helpful. In fact, students ranked these two methods as their second and third favorite after conferencing. Collective Feedback: I won’t sugarcoat this. Students will fight you on the idea of collective feedback. They seem to have a false perception that the problems of their peers are nothing like their own when, #realtalk, they all got the same issues, just varied in level. The way I make collective feedback work – and how I sell it to kids - is by pairing it with what I call a “Skills Day” - a lesson or minilesson designed to attack a weak skill. First, collective feedback looks like this in my classroom: As I read and score their essays, I keep notes of problems that I keep seeing. I then take those notes and analyze them for a predominant weak skill and a few quick fixes. The weak skill will be the target of my “Skills Day” minilesson, while the quick fixes are just matter for discussion when I present the feedback to the students. How I present the collective feedback is usually just an informal conversation while they fill in a progress monitor (hands down the fastest method), a quick powerpoint with samples from their writing, or sometimes, I’ll put together a Reader’s Report which is modeled after the Chief Reader reports for past exams. This is an overview of common mistakes I saw in their writing. I then move on to a skills lesson. (The skills lesson part is why collective feedback gets two clocks for time investment above). These are short and often involve students interacting with an exemplar essay or a strong example by their peers. Their actual essays only get a score, so their acquisition of feedback is based on their ability to invest in the “Skill Day” and transfer the skills. Small Group: Similar to collective feedback, small group feedback saves time overall but still requires some planning. Again, keeping notes as I read, I make note of common problems. I use a score roster with common issues listed beside each student's name which allows me to just circle as I read. Then I group kids based on their weakest skill and create small minilessons to re-teach. The idea of sitting down to write 4+ minilessons is daunting, but I keep it simple. Tell students to focus on their weak skill as they re-read their essay and those of the others in the group. Then open the table up for discussion on what would make their writing stronger and what they notice in the drafts. Simple. Re-read and talk. Don’t kill yourself making exciting interactive minilessons when simple works! The same methodology works if you just want to group students by their score. Both small group feedback and collaborative feedback have been particularly useful in the beginning of the year. At that point, students are working through the same issues and weaknesses in their writing, so the collaborative piece works well. Later in the year, I will sometimes have my stronger writers lead small groups or prepare collective comments to differentiate for their heightened ability. Most valuable to me in these methods is the level of student ownership. They put the work in. They do the talking. They learn. And best part, all I’ve written on drafts is a number. Sometimes, however, I find myself with only enough time to read and score. No time for “Skills Day” prep. No time to group students. I just need to read, score, and move. That’s when I employ my fastest methods: One Focus Feedback and Quick Annotation. One Focus Feedback: When I was a first year teacher, I was given a piece of powerful advice. My mentor (who just so happens to be the best teacher I know – lucky me!) pointed out that detailed feedback and notes all over a draft are usually just overwhelming for a student. They look at it as a failure, seeing all the things they did wrong. His advice was to move them in one area, to pick one skill that you can address. Six years later, I have embraced that mindset with my AP students. One Focus Feedback is simple. I read and jot an area of focus at the top of their paper. I might add a comment with where they can find it in the paper, but usually its just a couple words, jotted quickly. At the beginning of the year, I pair this method with collective feedback so students know what I mean when I write, “Weak Analysis; Body Paragraph 2.” As the year moves on, I put the interpretation of those comments on them because they know what those issues are and they know what it looks like from looking at samples and their own practice. Like I said: read, score, jot, and on to the next essay. This is particularly useful when I have kids writing FRQs every week. Quick Annotation: Annotating as a read is a great way to quickly provide feedback, but it only works if I can do it as a go. No stopping to re-read or comment. It has to be quick. To accomplish this, I use two methods, either highlighting or using feedback codes. The codes are simple. Here is my list of symbols and words to make quick notes. Give the kids the code sheet and they just need to look through on their own. Highlighting is equally time saving and again, focuses students on certain areas of their draft. If I’m really on a time crunch, I just highlight areas that need work. This might be a single word or an entire paragraph. It isn’t much in terms of detail, but if you ask kids to analyze the highlighted sections, they usually pick out the same problem you would. Sometimes, using this method, I’ll have them review essays with a partner who writes in the margins why that section or word is highlighted. Again, students interact with their writing more, but I am not killing myself writing all those comments myself. Conversely, I also use highlighting to boost students’ confidence. If I recognize students are getting discouraged, I do a “Positive Read.” I don’t put in a grade. I just score and highlight things they do well in the essay. They still have the assessment of the score, but instead of focusing on the bad, they can see what they are doing right. To be frank, sometimes it is difficult to pick out strengths, but if you frame your thinking relative to the overall essay, you’ll find something! And that is how I provide effective feedback without locking myself in my office for days at a time. Obviously some methods are faster than others, but I cannot stress how important it is for a writing instructor to employ all of them in the proper context. Here’s a quick chart (because I live for charts) to use as a guide, but your instincts are always best! I hope that helps. Refining my feedback practice is a journey I am still on. This is just a sample of what has worked for me. For you, I hope it will be just as successful.

Grading Hack #2: Collaborative Process Writing I love a good teaching myth. I’ve ignored them, believed them, and perpetuated them enough to know that they fill in all the cracks of the educational universe. Today, I’m here to debunk – and debunk profusely - the idea that collaborate writing (or really, any collaborative work) does not reap the same rewards for students. First, a definition of terms. When I say collaborative writing, I am talking about when students create written material in small groups, not edit, revise, or nod and pass. (While that is a valuable step in the collaborative writing process; it’s just not relevant for this post. We’re talking product). Collaborative writing has increased student growth (best AP scores yet!) and fostered the growth mindset I value as the teacher of a rigorous course. When offering collaborative writing as a solution to grading burnout, however, I usually get responses tied to the aforementioned myth.

To them, I would respond with the research of Carole H. McAllister, author of “Collaborative Writing Groups in the College Classroom.” Her results showed that “collaborative writing groups are efficacious; all students significantly improve their writing; retention rates for group classes are significantly higher than individual classes; and students enjoy writing more in (permanent and changing) group classes” (2005). Her study with college age students proved value on many levels when implementing collaborative writing. Nonetheless, each of these common responses from the nay sayers is grounded in logic and experience, but they are based on misconception. Collaborative writing has been an incredible tool for effective feedback and writing practice in my classroom, but more immediately relevant, it has allowed me to have kids write more for feedback without adding to my already hefty pile. This translated into noticeable student growth (and if that doesn’t convince any nay sayers, I might be talking to the wrong crowd). Like all good methodologies, this is not my own but stolen from someone else… who stole it from someone else. In an AP training last summer, the presenter suggested the model of collaborative writing I will share with you in response to concerns about the amount of grading required to create growth in student writing. Since this is a blog series on grading efficiently (and feedback), it seems relevant. It certainly seemed relevant to me a year ago because I implemented it the second week of school, and seeing the value in it, continued it throughout the school year. Here’s how it works: Collaborative WritingGrouping: Honestly, I’m just going to slowing back out of the room on this one and let the pedogogy experts fight it out. Heterogeneous or homogenous – I think both grouping methods have value. However, I don’t invest the time usually for this process. I randomly group the kids by numbering, games, lining them up, etc. I care more about diverse collaboration than ability level. THAT SAID, I would recognize and support either model – heterogeneous or homogenous – being used in different contexts.

I’m just gonna let other people – who have more knowledge on that matter - fight that battle. Just put your kids in groups of even size. Task: Assign a writing task, appropriate to your unit design. This can be quite varied as I have had students writing full AP Free Response Questions (FRQ), completing SOAPSTone charts, writing paragraphs, and even just pre-writing for task. Primarily, I find this most appropriate for formative assessment, or process writing. These collaborative writing tasks allow me increased time for feedback, so I often have students try out any major writing task collaboratively before jumping in to the full task. For instance, this last year, I had students write the Chavez AP Lang FRQ collaboratively before they were responsible for the Adams FRQ on their own. It’s was also effectively employed in checking pre-writing before they wrote individually on any topic. These “test runs” set kids off on the right foot when writing individually. In essence, it works with any form of writing task – which is why it works for immediate implementation. Process: The process is exactly what you think it is – the group works together to write something. The difference with this methodology is that there are some rules and outcomes that vary.

Benefits: The most obvious benefit of this method for writing is that it cuts your work down significantly. If I have students in groups of 5, then a class of 20 (Ha!) comes down to 4 drafts. With only 4 drafts, I can leave ample, detailed feedback which they can reflect on as a group or I can photocopy for their own reflection. It immediately and effectively cuts back on grading to allow for better feedback. Win. Beyond the obvious, though, there are many other advantages here. Consider the drafting process. By forcing students to agree on all writing decisions, they are asked to talk through and rationalize all those choices to the rest of the group. It fosters purposeful collaboration, but it also increased metacognition about their writing. This self-awareness about the writing task itself is powerful. Also, engagement is not a problem. No one wants to be the kids who isn’t keeping up only to be responsible for a weak paper picked at the end. In my practice of this method, students have all been focused on the task, pushing to keep on pace with their group. In AP world, this is great practice for writing under pressure. In all other realms, it is also good practice for monitoring progress of others and actively responding. The bottom line here is that students invest a lot more when there is a little healthy peer pressure to perform. Additionally, it practices transferring feedback from one task to the next. For instance, if I have a group collaboratively pre-write for an AP Language argument FRQ, it is with the understanding that they will be tasked with doing it themselves. Given this instruction, they pay attention to how those skills practiced with their peers align to those which will be assessed individually. It is subtle practice in skill transfer with a change in task. In response to collaborative writing nay sayers who worry about assessing the individual, the point is that not all assessment needs to be assessed individually, especially if it is for feedback. Rather, kids relish the chance to get feedback without a gradebook score. Collaborative practice instead hones their skills for when they are assessed individually, on a later task. Consider it like this: why read 100 introduction paragraphs (which you will ultimately read in their final draft of a research paper) when you can read 20-25, re-direct or assess for re-teaching, and get the better results? Process writing like this should have checkpoints for feedback or there will not be growth; we can’t let providing the feedback become a burden eclipsing that need. This collaborative model addresses this. Finally, the level of critical thinking within these groups will vary. As mentioned, some worry about the high level students taking the lead and silencing their lower ability group mates. This can happen – not surprisingly – if students are not either taught or told to balance the conversation between all members of the group. Furthermore, if that does happen, the lower level students are still following along, getting the tactile practice of writing out the draft. They may not say as much in the discussion, but they are engaged in a process which will bring them closer to proficiency on their own. You might also respond to any imbalance in the groups by adding additional rules. Maybe set a different leader for each body paragraph, or establish norms for how many times each person contributes, or declare that any one who interrupts another must take 5 minutes of silent time. Respond to this group work as you would any other, but in my experience, the assumed problems have not manifested as long as I was present and, as Dave Burgess suggests in Teach Like a Pirate, “immersed” in the activity. For me, grading has been a roadblock so many times that it pains me to think other teachers feel the same. In implementing effective collaborative writing, some of that strain can be alleviated for the benefit of kids. Ignore the nay sayers and myths about collaborative work, in this case writing, because this works! It eliminates some grading while simultaneously increasing feedback. What could be better than that? First things first. I am in love with two Twittersphere things at the moment: #BookSnaps and #TeacherStats. Without even really knowing the full story, I jumped on both bandwagons… (Kind of like the sad, awkward kid trying to make friends). But that’s not what I promised. I promised grading hacks, which is really the dangling carrot. As I mentioned in my previous post, I have made an intentional push to get my students writing MORE in the last couple years, largely in response to AP curriculum. In order to maintain whatever sanity remains along the way, I’ve been forced to find grading solutions to manage intake as high as 95+ essays every week. In this series, I want to start with my favorite: holistic grading. I’m starting here for one big reason. Holistic grading, while my favorite grading hack, requires the biggest shift in mindset about grading and feedback. It’s not for everyone, and I get that. For me, though, it is eeeeeverything. Why I Grade HolisticallyHere’s why I love it.

So, basically, I love using holistic grading. Fortunately for me, I have holistic scoring guides created by AP which I have adapted to general writing styles. Creating holistic rubrics isn’t difficult, however; it’s the preparation to use them which can be daunting. Therefore, I wanted to walk through the process I use, noting a few of the strategies I have found helpful along the way. How I Grade HolisticallyDon't panic! I never use all of these methods adjacent, but I do hit the basic steps in the process for each new holistic rubric.

This methodology seems time consuming, and it can be – especially at the beginning of the year. However, the process becomes internalized and the preparation lessens and lessens. It is additionally helpful that the rubric does not change much from one assignment to the next, making the expectations clearer as the year progresses. That said-- Grade Holistically, Only If...... you are willing to commit to the mindset so it is done with fidelity.

Holistic grading isn’t the fix-all some people think it is. As a member of a PD committee recently, we found that teachers craved holistic rubrics, but in practice, they seemed to fall flat with students. This emphasizes the important of preparation when using holistic grading. If you frontload at the beginning of the year, as I described above, and reinforce the expectations with students, holistic grading is the grading hack you always wanted. However, that said, it is obviously a yearlong commitment to do it properly. Additionally, holistic grading is not for process work, but summative. In my world, process work (draft checks, body paragraphs, etc) is meant for feedback, not a grade. It does no good to grade an intro paragraph holistically when you are trying to direct their specific revisions. Rather, feedback is appropriate. (In a later post in this grading hacks series, I’ll talk about how to manage that step of the process). Basically, just recognize when holistic is appropriate and when it is not. On-demand writing of any kind is great for holistic grading. Finally, the student perception of feedback from holistic grading is a challenge. Some students – most even – expect the details comments written throughout. Nonetheless, we know that pain of seeing those annotated drafts dropped in the garbage on the way out. As mentioned, I’ll talk about time saving feedback in the future, but holistic grading can only work as feedback if you have properly normed the levels of proficiency. It also requires you to foster a growth mindset with the students that move away from mastery of skills to overall improvement. Students need to understand the merits in moving from a 2 to a 4 or a 6 to an 8. In fact, I have found that holistic grading helps students recognize improvement a little more clearly (especially if you have them progress monitor!). It is the process work in between - with feedback - that is going to re-teach and re-direct. And that’s what I got. My WHY, HOW, and ONLY IFs of holistic grading. Like I said, it is more of a mindset change that needs to carry out throughout the year. But, if you do so with fidelity, it has been one of the biggest grading hacks of my experience. It makes it possible to get through 5 essays in 10 minutes, or 60 essays in just a couple hours. I'd rather spend the process work leading up to a summative take my time. After all, a summative assessment should be a student's best chance for success. I think I'll begin with a photo story... ... and I'll begin with a bold statement.

No one knows the pain of grading like an English teacher. Ok, that might be harsh. I’ll revise to say no one knows the pain of grading like a teacher with a writing focus. If you’ve assigned any writing assignment from a paragraph to a multi-page essay, you know the intimidation and dread that comes with the due date – when a stack of 100+ assignments ends up in your To Grade pile. My own pattern of denial looks like this:

Then, as I read (and complain some more), I question if the assignment was even worth it. Or rather, my significant other says something like, “Then stop assigning it!” His logic is funny to any seasoned English teacher, but as I observe the operations of my colleagues, I have noticed that some have adopted the same mentality. I even find myself considering it! The danger in this is that we start using grading as an excuse to assign less writing. My best work pal has struggled with this all year. Her PLC, Professional Learning Community, is prone to this kind of thinking. Instead of having kids write an essay, they’ll write a paragraph. Instead of checking student progress during the research paper process, they’ll just do one big grade at the end. Being responsible for the Pre-AP version of their course (and tragically micro-managed by me, the AP teacher), she has found herself fighting throughout the year for more rigorous writing instruction. The response has usually been the same – they don’t have time to grade it. And I get that! One paragraph - let alone an essay - multiplied by even 60 (or heaven forbid, 120) can be hours of work. Especially troublesome is that idea that you would read all those paragraphs and there is no grade to show for it, or rather, it’ll just be graded again in the summative assessment. Very quickly the excuses pile up, and it’s easy to see how they shift our thinking and move our practice away from writing. But it can’t. Being an AP teacher, I have been confronted with a heightened need for writing practice, especially when I compared my own practice to that of my peers. Some of them were assigning a Free Response Question essay every week! This year, that was 95 essays to grade every week. Sometimes, I managed to pull it off, especially leading up to the test, and as I mentioned in a previous post, I read 2000+ essays this year. However, the amount of writing I needed to get from students required me to push myself, and more importantly, find grading solutions that helped me keep grading manageable. Knowing the struggle I hear in PD, in department meetings, in PLC, I want to share out some of those solutions. To do it right, I’ll post a series over the next few days with step-by-step structures and tools I use in my classroom to re-prioritize and streamline the amount of grading I do. (Like I said, 95+ essays a week!). Come back for posts on 1) holistic grading, 2) collaborative writing, 3) self-assessment, 4) feedback methodologies, and 6) process grading. My intention is simple – to get kids writing more, but not at the cost of the amazing teachers out there. More writing. Less stress. No more sad grading pictures. Let’s do it! |

Archives

February 2024

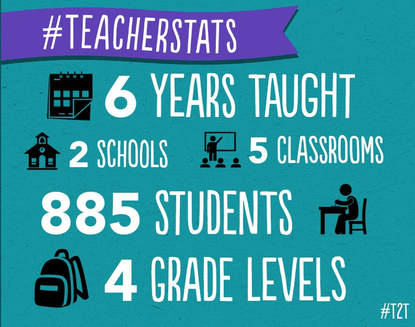

AuthorSteph Cwikla has been a teacher since 2012, focusing on ELA curriculum. Now, she also works as an instructional coach, helping other teachers improve engagement and instruction. |

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed