|

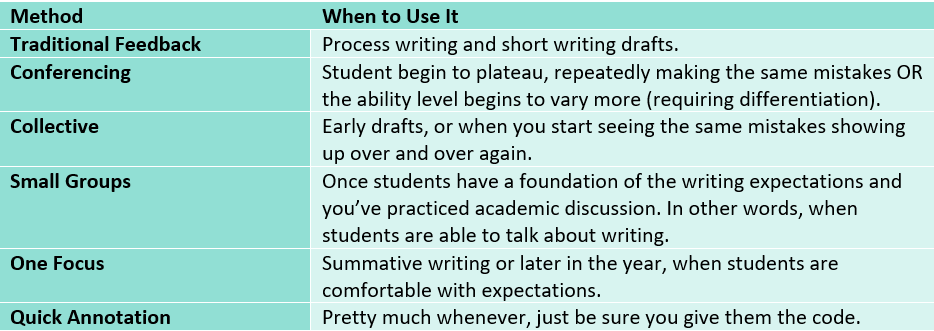

So my second way to cut back on grading is self assessment, and the good news is, I already posted on it! Check out how I embrace self assessment in my classroom to alleviate some of my grading here, in my Dear Grading, You Suck post. With that all wrapped up, I can move on to Grading Hack #4: Feedback Methodologies. (Sounds like a party, doesn’t it?) You may be wondering, how do different methods of providing feedback lessen my grading load? In fact, doesn’t additional feedback increase my time spent grading? I’m here to say it doesn’t have to. Most of the time we spend grading is usually dedicated to comments and notes we add to drafts and assignments to move kids in the right direction. This, in my opinion, is the most traditional type of feedback, but not necessarily the best method. To cut back on some of the time invested in this step - and therefore, cut back on time spent grading – I have adopted different methods of providing this feedback that move things a little quicker, and again, in my opinion, produce more significant student growth. Let’s dig into the methods I want share with you by comparing them on the time scale. I created a fancy little infographic to illustrate the time invested in each method. Forms of Feedback (by Time Invested)As you can see my methods vary in time investment, but all belong in effective writing instruction. The hack comes in knowing when to use each effectively. Let’s begin with the most time consuming ones: traditional feedback and conferencing. Traditional Feedback: There is nothing wrong with taking the time to write rich commentary on student drafts. In fact, I see this as a very important starting point with my AP students. I do, however, use it sparingly, and most commonly, with process writing. As I build students toward a full AP Free Response Question, I will provide this detailed feedback on outlines and paragraphs (and nothing longer than that!). In all honesty, I reserve this method almost exclusively for the collaborative writing I discussed in my last point. When they are short or fewer drafts, traditional feedback is manageable and effective. The traditional detailed annotation of traditional feedback is powerful; it just needs to be used in a feasible context. Conferencing: Requiring the same investment of time as traditional feedback (possibly even more), conferencing also has its place and is probably the most powerful with young writers. When surveyed at the end of the year, the highest percentage of my students found conferencing most helpful in improving their writing. As we all know, though, the amount of time needed to effectively conference with students is incredible. Last year, I recall setting aside three days of class time for conferencing, only to find out I could maybe get through about five in a day – unsuccessful with a class of 30. Similarly unsuccessful (or more so, impractical), setting up conferences outside of class completely devoured all my prep time. Nonetheless, conferencing has to happen in a writing focused classroom. Just like with traditional feedback, I have found that it is simply about finding the appropriate time to utilize it. This school year, my fellow AP teacher and I agreed to a schedule where every other week, we’d send out a Google doc with conference time slots for the kids to claim. These were weeks following timed essays (AP FRQs) so that students could bring their most recent, scored essay for one-on-one discussion. Limiting the conferencing to every other week kept it more manageable as we could plan our prep time accordingly. We also offered this option primarily in the middle of the year: quarters two and three. After discussing when this method would be most impactful, we decided that they needed to begin with a basic understanding of the material before conferences would even be practical; hence, we didn’t send out the sign ups first quarter. Then, as we got close to the AP exam, we wanted them to be more independent in their evaluation of their writing, so we stopped sending out the sign up sheet fourth quarter. At any point, I encourage my kids to come see me about their writing, but this created a period focused on conferencing that was much more practical than attempting it all year long. As for as the practice of conferencing, there are people much wiser than me on the topic to guide you (See: Write Beside Them by Penny Kittle). My method - which fortunately requires no prep - has usually been to read through the essay with the student, stopping to discuss weaknesses and strengths. Students can amazingly hear the issues in their writing as soon as it’s read to them. Moving on, the next two methods – small group and collective feedback – have proven to be incredibly helpful. In fact, students ranked these two methods as their second and third favorite after conferencing. Collective Feedback: I won’t sugarcoat this. Students will fight you on the idea of collective feedback. They seem to have a false perception that the problems of their peers are nothing like their own when, #realtalk, they all got the same issues, just varied in level. The way I make collective feedback work – and how I sell it to kids - is by pairing it with what I call a “Skills Day” - a lesson or minilesson designed to attack a weak skill. First, collective feedback looks like this in my classroom: As I read and score their essays, I keep notes of problems that I keep seeing. I then take those notes and analyze them for a predominant weak skill and a few quick fixes. The weak skill will be the target of my “Skills Day” minilesson, while the quick fixes are just matter for discussion when I present the feedback to the students. How I present the collective feedback is usually just an informal conversation while they fill in a progress monitor (hands down the fastest method), a quick powerpoint with samples from their writing, or sometimes, I’ll put together a Reader’s Report which is modeled after the Chief Reader reports for past exams. This is an overview of common mistakes I saw in their writing. I then move on to a skills lesson. (The skills lesson part is why collective feedback gets two clocks for time investment above). These are short and often involve students interacting with an exemplar essay or a strong example by their peers. Their actual essays only get a score, so their acquisition of feedback is based on their ability to invest in the “Skill Day” and transfer the skills. Small Group: Similar to collective feedback, small group feedback saves time overall but still requires some planning. Again, keeping notes as I read, I make note of common problems. I use a score roster with common issues listed beside each student's name which allows me to just circle as I read. Then I group kids based on their weakest skill and create small minilessons to re-teach. The idea of sitting down to write 4+ minilessons is daunting, but I keep it simple. Tell students to focus on their weak skill as they re-read their essay and those of the others in the group. Then open the table up for discussion on what would make their writing stronger and what they notice in the drafts. Simple. Re-read and talk. Don’t kill yourself making exciting interactive minilessons when simple works! The same methodology works if you just want to group students by their score. Both small group feedback and collaborative feedback have been particularly useful in the beginning of the year. At that point, students are working through the same issues and weaknesses in their writing, so the collaborative piece works well. Later in the year, I will sometimes have my stronger writers lead small groups or prepare collective comments to differentiate for their heightened ability. Most valuable to me in these methods is the level of student ownership. They put the work in. They do the talking. They learn. And best part, all I’ve written on drafts is a number. Sometimes, however, I find myself with only enough time to read and score. No time for “Skills Day” prep. No time to group students. I just need to read, score, and move. That’s when I employ my fastest methods: One Focus Feedback and Quick Annotation. One Focus Feedback: When I was a first year teacher, I was given a piece of powerful advice. My mentor (who just so happens to be the best teacher I know – lucky me!) pointed out that detailed feedback and notes all over a draft are usually just overwhelming for a student. They look at it as a failure, seeing all the things they did wrong. His advice was to move them in one area, to pick one skill that you can address. Six years later, I have embraced that mindset with my AP students. One Focus Feedback is simple. I read and jot an area of focus at the top of their paper. I might add a comment with where they can find it in the paper, but usually its just a couple words, jotted quickly. At the beginning of the year, I pair this method with collective feedback so students know what I mean when I write, “Weak Analysis; Body Paragraph 2.” As the year moves on, I put the interpretation of those comments on them because they know what those issues are and they know what it looks like from looking at samples and their own practice. Like I said: read, score, jot, and on to the next essay. This is particularly useful when I have kids writing FRQs every week. Quick Annotation: Annotating as a read is a great way to quickly provide feedback, but it only works if I can do it as a go. No stopping to re-read or comment. It has to be quick. To accomplish this, I use two methods, either highlighting or using feedback codes. The codes are simple. Here is my list of symbols and words to make quick notes. Give the kids the code sheet and they just need to look through on their own. Highlighting is equally time saving and again, focuses students on certain areas of their draft. If I’m really on a time crunch, I just highlight areas that need work. This might be a single word or an entire paragraph. It isn’t much in terms of detail, but if you ask kids to analyze the highlighted sections, they usually pick out the same problem you would. Sometimes, using this method, I’ll have them review essays with a partner who writes in the margins why that section or word is highlighted. Again, students interact with their writing more, but I am not killing myself writing all those comments myself. Conversely, I also use highlighting to boost students’ confidence. If I recognize students are getting discouraged, I do a “Positive Read.” I don’t put in a grade. I just score and highlight things they do well in the essay. They still have the assessment of the score, but instead of focusing on the bad, they can see what they are doing right. To be frank, sometimes it is difficult to pick out strengths, but if you frame your thinking relative to the overall essay, you’ll find something! And that is how I provide effective feedback without locking myself in my office for days at a time. Obviously some methods are faster than others, but I cannot stress how important it is for a writing instructor to employ all of them in the proper context. Here’s a quick chart (because I live for charts) to use as a guide, but your instincts are always best! I hope that helps. Refining my feedback practice is a journey I am still on. This is just a sample of what has worked for me. For you, I hope it will be just as successful.

1 Comment

|

Archives

February 2024

AuthorSteph Cwikla has been a teacher since 2012, focusing on ELA curriculum. Now, she also works as an instructional coach, helping other teachers improve engagement and instruction. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed