|

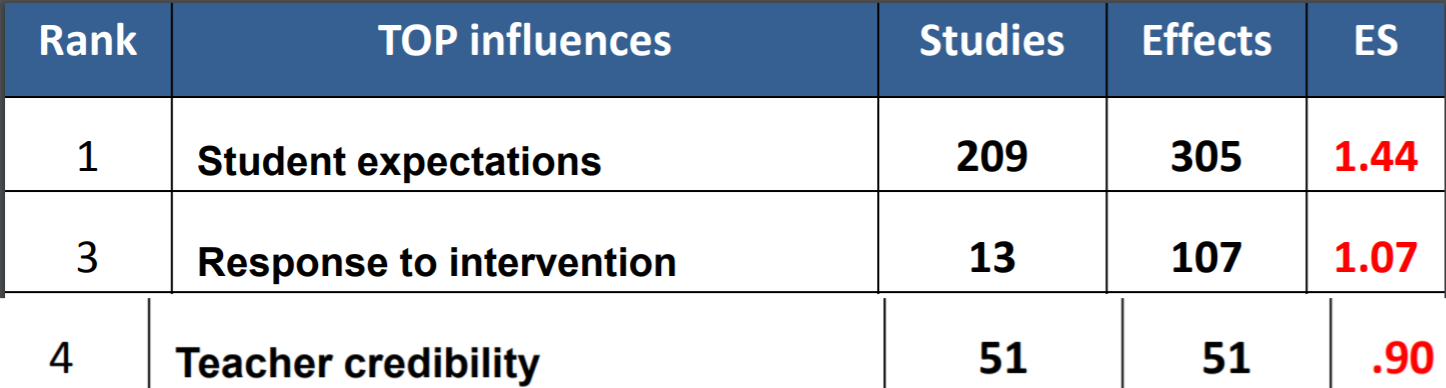

Hello again! After a year of posting my lesson plans, I am so excited to be back, posting for a new year. As is my nature, I will turn things upside down this year, but I promise to keep posting new materials to help other teachers out there find their own success. To be more specific, this year I am embarking on personalized instruction, meaning that curriculum will be catered to student need and choice. It will be flexible (which is my nightmare). It will be hard (which is my M. O.). But it will also be such an adventure. But more about that later. Today, I want to talk about writing for the not-so-confident writing teacher because my lovely colleague (like, the colleague that goes above and beyond for EVERYONE … and their cousin) is taking on senior composition and asked for my help. I figured I would compile my "wisdom" for you at the same time. So that’s the plan. Now, I am not your traditional English teacher. I don’t really like to read. I like to talk about novels and characters and all that, and I like to write about them even more. However, unlike most of my peers, I do not relish the idea of sitting down and reading a book. In fact, I force myself to do it only to model for my reluctant readers. It was never the idea of reading The Crucible every year that got me into English education. It was writing. While other teachers were finely honing their skills with teaching literature, I (honestly) skipped my reading assignments and devoured all the material I could on writing. (I do not condone not doing the reading, but in no way am I worse person because I SparkNoted Oliver Twist. Just sayin'). Over time, this passionate pursuit helped my pick out my fundamental writing practices. That's not to say I am some writing expert, but having taught primarily composition courses throughout my career, it is where my strength lies. And throughout that experience, I have learned a few fundamental things about writing instruction. Here they are… Students (and You!) Should Write Every Day.In a traditional English class, where we are torn between reading, writing, grammar, AND speaking and listening, setting aside time to write every day always gets sacrificed. However, if possible, this is such a valuable use of time. It helps build relationships with students, uncovers what they are passionate about, and builds emotional awareness that is invaluable. All while providing essential practice. It’s also probably the only time they’ve been allowed to just write whatever they want in years, if you give them the option. That freedom is powerful and creates authentic writing that doesn’t happen often. Furthermore, it gives you a rare chance to write with them. As a young teacher, I thought I had to hold students accountable by wandering around the room and watching over their shoulders, but that’s not the only way. (And frankly, at nearly 6 feet tall, I usually intimidate them). Rather, sit down and write with them, and if you’re feeling brave, SHARE what you wrote. That vulnerability breaks down a lot of walls that the education system has put up between teachers and students. When you write about the terrible morning you have or even that fact that you yourself don’t feel like writing, it shows students how all of that is part of the process and (shocker!) that you’re human. Students like human teachers, and being open with them in this way, adds to your own credibility. And, if you didn’t know, that is one of the few things that actually impacts student success: their perception of the teacher’s credibility. (See below) Students need to see #thestruggle.One of the scariest things for me as a young teacher was the idea of getting up on the document camera and modeling how to write something. In fact, I was prone to writing out full samples with all my ideas laid out before I got up and showed them how to do it. What this created was a scripted model that, frankly, didn’t produce much in terms of results. I had always been told that modeling was an incredibly effective instructional method, but somehow, it just produced lackluster, formulaic writing. And it’s no wonder. I was giving them the exact formula. I had sat down and written out the entire model, making sure every step was clear and well-laid out. In doing so, I showed them inauthentic writing. I gave them vanilla writing when I wanted rocky road. That’s why they need to see you struggle a bit. If we display writing in a perfectly outlined, error-free way, that’s what they think it is supposed to look like, and we all know that isn’t how good writing happens. We revise. We cross out entire sections. We start over! Students need to see that all writers - even their “expert” English teacher - muck it up sometimes. It helps them feel more confident in their writing while still walking them through the process. Students need one-on-one time.Every time I have asked my students what kind of feedback they found most helpful, the answer is conferencing. And I would guess that every teacher sees the value in one-on-one time. We all, however, face the obvious time constraint. How do you take any individual time with a student when there are 29+ other kids in the room? It’s a fair question. One that I battle with weekly, if not daily. It’s honestly my primary motivation for the move to personalized learning. I want that time to sit down and talk through students’ work. To make it happen, it takes a fair amount of ground work. For instance, the first week of school, we’ll talk at length about expectations for what I call “Breakout Time.” They will create their own rules for the time, and then they can keep one another accountable while I’m working with their peers. This, of course, also takes a safe culture where they are invested in one another’s success. (Something else that needs to start Week 1). The next obstacle is people don’t know what to do in these conferences. The simplest way to start is just assessing the work with the student sitting there. Because I work in the AP world, I like to read through their essays, stopping to point out gaps, weaknesses, and strengths in the writing, and then, I’ll simple explain why the essay gets the score I assign it. Basically, it’s a think aloud of your own grading process (which also means you don’t have to grade it on prep). Start simple and work your way up to more complex writing conferences about growth and writing nuance. They don't need to be perfectly designed. They just need to happen. Students need to write together. In recording my lessons from the last year, I utilized what I call Collaborative Writing multiple times. The process is simple. Instead of having kids work on one piece of paper, or one draft, they all write exactly the same thing on their own sheet of paper, each with everyone’s names. At the end of the given time, I pick up one of these sheets at random. This forces kids to work through a draft sentence by sentence, talking about the best possible way to present an idea and coming to consensus about what needs to be written. It’s not a fast process. I’ll tell you that. It takes about twice as long as a normal draft, but that’s because they labor over every word and sentence so that they are all in agreement. Their conversations are about writing purpose, style, and development. Instead of everyone staring at one kid writing on a piece of paper, they are talking about it in a way that brings out their best. In my experience, I like this process in both mixed and homogenous groups. Mixed groups allow more sophisticated writers to talk their peers through the weaknesses in their ideas. Homogenous groups allow students to see other students struggle with the same things. Both have been successful and both bring forth profound conversations about writing. Students need a little pressure with their writing.Now this is an #unpopularopinion with many of my own colleagues. We hate the pressure of standardized tests that ask students to sit down and come up with something impressive in 40 minutes. (I’m looking at your AP, SAT, and AP). But, the more I have explored this as an AP teacher, the more benefit I see in on-demand writing. As an English teacher, I find myself asking my non-teacher friends (all three of them) about the type of writing they do in their jobs, and I think about the non-classroom writing I do for my own. This, along with my higher education experience, has taught me that being able to formulate and compose ideas quickly is a very valuable skill. From realizing you have a one page reflection due in 20 minutes to throwing off an email between classes, I have utilized on-demand writing skills countless times. Preparing students for this reality is a huge advantage with on-demand writing. There is also the benefit of not having to track down missing work. While there are some unavoidables like the absent kid or the rare one sentence on the page kid, collecting writing after a set time means you get something from every kid in the class. It may not be pretty. It may need more work, but at least you have something to assess them from. That said, I feel equally passionately that any on-demand writing should be reworked if needed. Revision is the truest way to become a stronger writer, so all on-demand writing, because it is completed on a time crunch, should be afforded the chance to improve. Students should write for real people (because teachers are obviously, not real). This is simple. Students work harder for real people. If I tell them that their essays are going to be read by a college composition teacher, they will try a bit harder. If I tell them the work will be submitted for a contest, they’ll work even harder. That’s just how it is. (Imagine how motivated they get when there is a cash prize for the contest). While you won’t always be able to find or create these authentic experiences, any time you can, DO IT! You’ll see a fire lit under their butts that you’ve never seen before. Just be sure to put your ego in check. The reality is that they don’t always care what you think, but they really care what “real world” people think. (Prepare yourself for that hit to the ego now.) Here are some great authentic writing options you can work in: Students need to see writing done well.Even if the course is designed as a composition class, like my colleagues', that doesn’t mean they shouldn’t be reading as much as they write. Students need a roadmap for the difficult writing tasks we set out for them, either from expert, published writers, other students, or you. As someone who enjoys writing, I like creating my own samples, but I love to pair them with published work. (It also gives students a little more insight about me). The biggest objection I see when it comes to mentor texts is the fear that students just mimic or even copy the mentor text. And that is the reality, especially with grade obsessed little sweeties like my AP kids. They want to do it “right” and that makes them cling to the mentor text. This is where the modeling step can be profoundly helpful. In writing my own samples, I’ll explain how I am taking some ideas from the mentor text: “I like how they start with an anecdote, so I think I’ll do the same.” I also, however, explain where I go off on my own limb: “I like the idea of breaking a memoir narrative into short vignettes, but my story is more interconnected, so it might make more sense to structure it as a unified narrative.” Providing multiple mentor texts can also accomplish this. I intentionally choose student samples each year that took their own spin on a mentor text or went in a completely different direction, even if the writing isn’t as sophisticated as another sample. Showing them the value of risk and creativity encourages them to take chances with their own writing. Below are three mentor texts for personal narrative: a published work, my own sample, and a student sample. Students need to understand the process of writing.The final, and maybe most important, aspect of writing to impart on students is that the writing process never ends. Even when the deadline comes, it just means that the draft was the best it could be at that moment. The potential of that draft is infinite. Penny Kittle and Kelly Gallagher illustrate this by referring to summative drafts as “Best Drafts” to show that revisions and editing should never stop. It is ongoing. Therefore, revision is essential in a successful writing class. I referred to this briefly before, but revision teaches more than you can as a teacher. Asking a student to simply read a draft aloud one more time can show them silly mistakes and awkward wording better than a red mark on a piece of paper. Asking students to read the writing of their peers can help them see where they can go, but also that their challenges are also the challenges of others. Offering revision of all writing has created a remarkable shift in my classroom. I set deadlines for these revisions as well as tasks they must complete before they can revise. This, first of all, limits the amount of re-scoring I have to do, but also forces the kids to really think about the changes they should be making to the writing. Some of my “before you can revise” activities include: recording a reading of the draft, coming in for a writing conference, annotating the draft based on a revision guide, and peer revision. Second, allowing revision has all but ended my parent complaints. (I’m frantically looking for wood to knock on and cringing as I even write that). Students know from the beginning that they have the opportunity to revise, and it’s their choice if they want to take that opportunity. When they choose not to and their grade drops, I refer parents to these opportunities and the responsibility falls back on the student (as it should). And there it is. All the wisdom on writing that I possess. All of it. I hope, as you read them, these things seem familiar - basically, they’re just best practice - but moreso, I hope that I have silenced some of those voices in your head that say its impossible. Because, it really isn’t. I am no super teacher, making everyone else in the building marvel at what I can accomplish. I am just an English teacher tucked away in a corner making the most of the time I got with kids, and not once have I nailed all of these things all year, every day. I’ve instead added something to the list each year and hoped for the best, so if you are feeling overwhelmed (Me. All the time.), try adding one of these writing practices. It’s a marathon, not a sprint. sincerely, cwik

1 Comment

|

Archives

February 2024

AuthorSteph Cwikla has been a teacher since 2012, focusing on ELA curriculum. Now, she also works as an instructional coach, helping other teachers improve engagement and instruction. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed